In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. All praise is due to Him, and may His peace and blessings be upon His final Messenger, Muhammad.

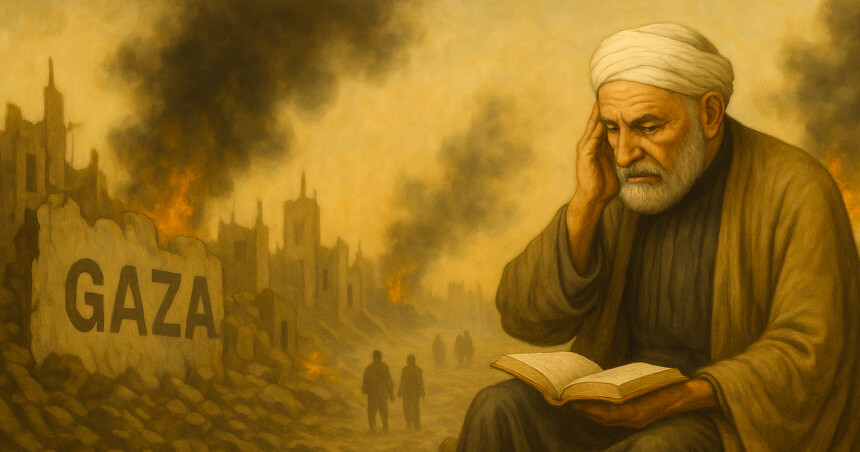

We live in troubled times, this is an era where the cries of the massacred are causing us to lose our hearing; it is where shells of treachery are raining down upon innocent heads, and where blood is mingling with soil and rubble in the streets.

This latest barbaric Zionist aggression waged against the besieged people of Gaza has continued for over six hundred days.

How and why have we become numb?

As this time has passed, it is as if we have become numb to the pain our brothers and sisters are feeling, as if we have gotten used to the depravity with which the occupation forces commit their brazen crimes, day in, day out.

This has not only occurred among our congregations but, more shockingly, has even seeped through to our Islamic scholars, our ulamā.

This state of affairs is unacceptable; ulamā are the inheritors of the Prophetic tradition.

As scholars, we are expected to be the vanguard, not laggards; leaders, not spectators; present in collective consciousness, not withdrawn into corners of jurisprudential debate.

Seeking knowledge isn’t an excuse for silence

Gaza is a defining issue of our times.

To shy away from it in the midst of genocide, in the name of jurisprudence and seeking knowledge, is not an option.

I do not wish to diminish the status of scholarly research or the study of jurisprudential matters by any means, every science has its place. But, if jurisprudence is truly our aim, then understanding context and setting priorities according to Allah’s ways during trials and calamities comes first and foremost.

What we are experiencing today in Gaza is a humanitarian catastrophe, a civilisational crisis, and a real test of the scholar’s function within the Ummah.

On which side do we truly stand?

Throughout Islamic history, great calamities have revealed the position of scholars and students of knowledge for their people.

Consider Imam al-‘Izz ibn ‘Abd al-Salām (d. 1262). When the Mongols advanced and suffering intensified, he did not refrain from speaking truth to power.

As Chief Judge of Egypt, he issued a legal ruling that corrupt Mamluk officials who had gained wealth illegitimately should be stripped of their positions and their assets returned to the public treasury.

When they resisted, he literally auctioned them off according to Islamic law governing the status of military slaves, forcing even the Sultan to pay their “price” to restore legitimate governance! He then mobilised the masses for jihad and resistance.

Similarly, Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328) personally entered the battlefield, encouraging people and strengthening soldiers, refusing to hide behind jurisprudential debates or theological arguments.

And yet, when faced with these examples of our predecessors, we find ulamā in the United Kingdom and elsewhere today, who will not even advise their congregations to protest and take other actions within the law that any citizen can do in support of Palestinian rights.

Scholar’s dilemma: relevance vs. retreat

Worse still, there are students of knowledge who continue to repeat old patterns of absence, resembling those recorded in history books about the fall of al-Andalus, where some jurists debated the ruling on a Hanafi marrying a Shāfi’ī as Muslim cities fell to the enemies of Islam.

To re-tread such footsteps is to risk irrelevance. After all, people of conscience — Muslim and non-Muslim — are nobly taking action, joining marches for Palestinian rights on Western streets and beyond.

Actions of this positive kind have helped yield excellent results so far. European countries including Spain, Norway, Slovenia, and Ireland have all taken diplomatic steps in support of Palestine, by recognising the country. [1] [2]

In fact, the Zionist entity has even since vacated its embassy from Dublin!

However, Islamic scholars appear to me to have been rather distant from these movements.

Price of scholarly silence

To see the Ummah’s ulamā — those who should be leading from the front — absent from the scene or preoccupied with issues inappropriate for our current circumstances signals a double danger:

There is a loss of people’s trust in scholars on one hand, and opening the field to alternative leaderships (which may be unqualified or harbour harmful agendas) on the other.

Ibn al-Qayyim’s observation comes to mind:

People relate to scholars in three ways: reformers guided by Divine guidance — these are the inheritors of the prophets; followers of apparent knowledge who do not act upon it; and traders in knowledge who care only about what they gain from it.”

Which category do we choose to belong to?

When knowledge becomes a veil

Scholarly laxity during such calamities cannot be explained merely by stagnation, but by departure from the essence of the Divine message.

Seeking knowledge is worship in itself, but it becomes evidence against its possessor if it is disabled from achieving its purposes.

Imam al-Shātibī wisely observed,

Any knowledge that does not produce action has nothing in the Sharī’ah to indicate its consideration.”

How can it be acceptable for a people to be exterminated before our eyes — its mosques bombed, its sick besieged, its children dying of hunger — whilst our scholarly discourse remains centred around seasonal issues?

Disputes over the time of breaking fast, the ruling on one who shaves before Eid al-Adha, or extensive criticism of intellectual movements at inappropriate times?

Prophetic model of engaged scholarship

Effective da’wah, teaching, and leadership all rest on relevance. As ulamā, we must speak from within people’s lived reality — not above it.

We must root the eternal in the everyday. This principle, embodied by the Prophetic model and carried by history’s greatest scholars, calls us to transform our approach fundamentally.

Scholars’ pulpits should become the lighthouse of awareness, their lessons circles of revival rather than regurgitation, their minds occupied with developing practical solutions, pressure plans, community initiatives, and support projects for the people of Gaza and other bleeding parts of the Ummatic body.

Those unable to descend into political or social action fields should make their pen a voice, their word a weapon, and their pulpit a front.

Reclaiming the Prophetic voice

The upper and lower limits of scholarly engagement — a framework familiar from Ibn al-Qayyim’s works — demand careful balance.

The upper limit involves direct political engagement and social activism; the lower limit requires, at minimum, that our discourse addresses the crisis meaningfully.

Neither extreme detachment nor inappropriate politicisation serves the Ummah’s needs. Contemporary Islamic scholarship must develop new approaches that honour both intellectual rigour and Prophetic relevance.

This means:

Changing how we think

Moving from academic isolation to engaged scholarship that speaks to contemporary crises whilst maintaining scholarly integrity.

Building better skills

Cultivating abilities to translate complex theological concepts into accessible guidance for people facing real-world challenges.

Creating useful tools

Developing concrete frameworks for community action, whether through direct support, advocacy, or consciousness-raising.

The moral imperative

I do not wish to call for excessive politicisation, nor for the abandonment of jurisprudential scholarship.

Rather, I wish to appeal to readers of reason and conscience, that knowledge which does not touch the Ummah’s pain amounts merely to preserved papers.

This is not falling into the trap of trivialising knowledge or diminishing its discussions, but demanding that scholarly discourse rise to the level of events, and that scholars reclaim their leadership role rather than following public mood or remaining prisoners of university seminars or closed pulpits.

If those who bear knowledge are not found defending the oppressed, where should they be found? The genocide in Gaza is a political crisis and a fundamental test of whether Islamic scholarship retains its Prophetic soul or has become merely an academic exercise divorced from Divine purpose.

The choice before contemporary Islamic scholarship is clear: will we be inheritors of the prophets who spoke truth to power and stood with the oppressed, or will we join the ranks of those whom history remembers as silent spectators to injustice?

The very essence of human dignity is under assault, so neutrality becomes complicity, and academic detachment transforms into moral failure. The people of Gaza, and indeed all oppressed peoples, deserve better from those who claim to inherit the Prophetic legacy of justice, compassion, and truth.

The time for scholarly silence has passed. The time for Prophetic voice has come.

Source: Islam21c

Notes

[1] https://www.islam21c.com/news/spain-norway-ireland-recognise-palestine/

[2] https://www.islam21c.com/news/slovenia-support-for-palestine-more-than-statehood/