In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. All praise is due to Him, and may His peace and blessings be upon His final Messenger, Muhammad.

The period of Moorish Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula — present-day Spain, Portugal, and Gibraltar — known as al-Andalus (711-1492), is one of many jewels in the crown of Islamic history.

No historical age is a utopia, humans had shortcomings in the past as they do now. But al-Andalus has been celebrated as a time of scholarly excellence, cultural splendour, and for its periods of peaceful coexistence between different peoples including Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

What some students of this era may not know, however, is that this legacy lives on today across Europe in bricks and mortar.

BACKGROUND

- The battle against Islamophobic misinformation in the West is constant, so it’s always worth equipping ourselves with visible evidence when making the case for our faith

- al-Andalus, the period of Moorish Muslim rule in Spain and beyond (711-1492), is full of examples of architectural prowess

- This was enthusiastically celebrated by the revival periods that followed in Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries

- By looking at Moorish Revival architecture, we can get a useful sense of who has admired and acknowledged Islamic civilisation in the past and why, not to mention how this is important in our present times

- This legacy should also serve as a reminder for Muslims to look at the bigger picture; our efforts may not yield results in our lifetime, but we can make an impact that is appreciated in the Dunya long after we have left it, and it is the Ākhirah we seek after all

Wondrous architecture from this period still abounds in Andalusian cities, from the Great Mosque or Mezquita of Cordoba, to the iconic hilltop Alhambra palace complex in Granada.

These places are widely celebrated! The Alhambra is among Spain’s most visited monuments. But the footprint of the architectural tradition that these awe-inspiring structures and others like them represent has been larger still.

One such impact, often born of sincere admiration for Iberian Muslim history, is visible in the “Moorish Revival” style, sometimes called “Neo-Moorish” or “Pseudo-Moorish”. This peaked in Europe in the 19th century.

al-Andalus is one of several Islamic civilisations that inspired the style, and its influence is apparent in many later houses of worship. What may surprise some, is that these buildings belong to the Islamic, Jewish, and Christian traditions.

From Syrian styles to Moorish motifs

Before we look at the Moorish Revival style, let’s get a better idea of the motifs that it “revived”.

Get ready to see a lot of spectacular arches! Unsurprisingly, the Cordoba Mezquita and Alhambra of Granada boast many beloved features of traditional Moorish architecture, making them a good place to start.

The Mezquita was built between 785-786, during the reign of Abd al-Rahman I — a Syrian prince in exile — who established a new emirate centred on Cordoba, after escaping the Abbasid family who had unseated and replaced his Umayyad dynasty, taking over the vast empire.

After establishing himself, the emir made Spain his home away from home. Abd al-Rahman personally oversaw the construction of his new mosque, which borrowed, for instance, from the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus. [1]

Perhaps the most important example of this appears in the Mezquita’s former prayer hall which features mesmerising arcades of horseshoe arches.

Dazzling double-decker arches

Where the Cordoba Mosque differs from its Syrian counterpart, however, is that its arcades boast an entire second tier of horseshoe arches above the first.

Moreover, the Mezquita’s arches use brick and limestone to give an alternating red and white pattern effect in keeping with Abd al-Rahman’s dynastic colours.

The emir’s successors made their own additions to the mosque too, expanding the hall and its arcades to include a total of 1,293 arch-topped pillars, sometimes compared to a forest today. [1]

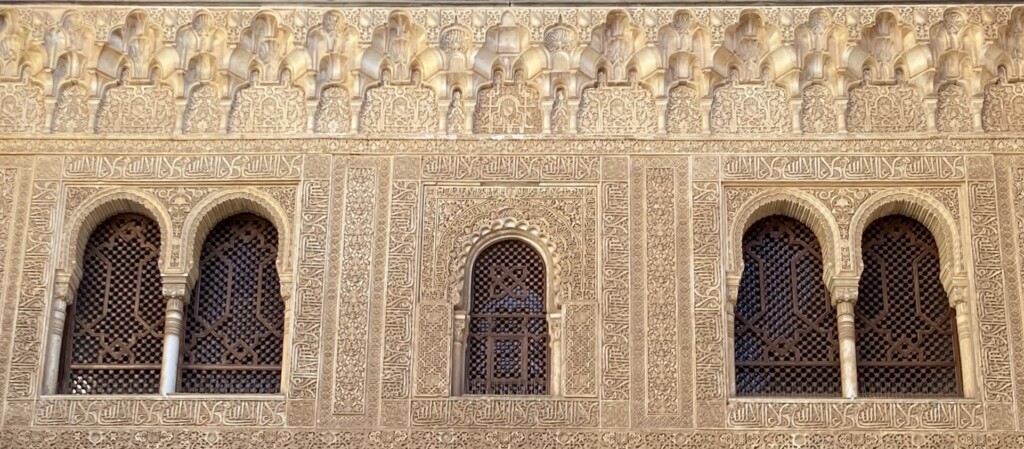

While the horseshoe arch is clearly the Mezquita’s main decorative motif — as shown not only by these arcades, but also by its prayer niche or mihrāb — the magnificent structure incorporates numerous other arch types as well.

As seen above, the mosque’s gate showcases a range of arches combining symmetrical arches with three lobes (trefoil) and other odd numbers (multifoil), as well as pointed arches and, of course, that favoured horseshoe shape.

Cordoba Mezquita: the world’s second-largest mosque after Masjid al-Haram until 1617

Having been converted into a Roman Catholic cathedral after Cordoba fell to King Ferdinand III of Castille and Leon in 1236, the Mezquita is no longer in use as a mosque today.

Nonetheless, its Islamic architectural features are integral to its identity, and remain heavily visible even today, arguably affording it the reputation as the Western world’s greatest Islamic building.

For centuries, the structure held pride of place as the world’s second-largest mosque after Masjid al-Haram in Makkah, right up until the Ottomans completed Istanbul’s Blue Mosque in 1617. [1]

The Alhambra

If Cordoba’s Mezquita is the jewel of al-Andalus’ earlier centuries, then the Alhambra is undoubtedly the pearl of the period’s later years.

The palace complex was built by the Nasrid dynasty who ruled Granada from 1238 until the end of Moorish rule in Iberia in 1492.

The Alhambra — literally “the Red One” in Arabic, named after the bricks used to build it — has an austere fortress-like exterior, but its lavish interior is altogether quite different. [1]

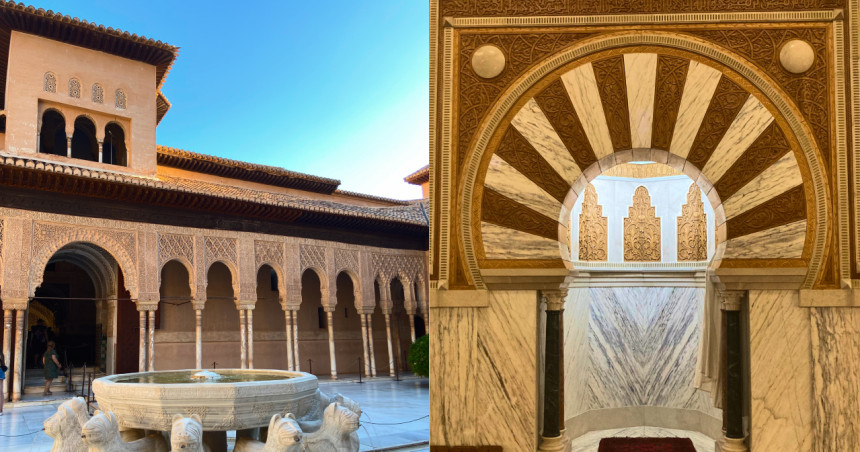

The palace boasts beautiful gardens, colourful tiles, and luxurious lattice windows. But its Patio of the Lions and Court of the Myrtles are perhaps the complex’s most famous areas, with their opulent water features and elaborately ornamented arcades.

As apparent in both the court and the patio space, one of the Red One’s most awe-inspiring aspects is its mind-blowing plasterwork.

In fact, plaster decorations adorn almost all of the palace’s surfaces, from the arches, to the walls and even the ceilings! [2]

The plasterwork showcases magnificent patterns and Islamic inscriptions, from Qur’ānic verses to the Nasrid dynasty motto, “Wa la ghalība illa Allah”, meaning “And there is no Victor except Allah.”

Indeed, it is as if Allah has granted al-Andalus an additional and long-lasting cultural victory by allowing these motifs to spread far beyond its former borders, and centuries after its time through the Moorish Revival.

Islamic synagogues?

Some later European buildings were even inspired directly by the Alhambra itself.

One in particular that comes to mind is Berlin’s Oranienburger Strasse Synagogue, also known as the New Synagogue. Built between 1859-1866, the façade was based on the Alhambra. [1]

This Jewish house of worship is one of many established by Central European Jewish communities back in the 19th century.

For many German and Austro-Hungarian Jews, this time was a period of gradual emancipation and greater freedom, where their respective governments ultimately granted them equal rights before the law. [3]

Sadly, changes in official status did not translate into an end to the harsh anti-Semitism present in European societies.

Despite these challenges, Jewish communities used their newfound rights to build synagogues.

Interestingly, well aware of how Judaism had historically flourished in Muslim societies — including al-Andalus — these communities consciously included Islamic influences in these new buildings, adopting domes, arches of various kinds, minaret-like towers, and more.

In doing so, Europe’s Jews used such architecture not only to harken back to this glorious past of tolerance and co-existence, but also to highlight their new place in society.

Though destroyed by allied bombs in 1943 during the Second World War, the Berlin synagogue’s exterior has since been restored.

Tragically, many historic Moorish Revival synagogues did not survive Nazism, but some are still standing, for instance in Sarajevo, Budapest, and even Bradford. [4]

Iberia may be far from Bradford, but its influence went further yet, crossing the Mediterranean.

The Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II (r.1876-1909) for instance — ever the skilled carpenter — personally carved wooden lattices inspired by the Alhambra to decorate the Yıldız Hamidiye Mosque in Istanbul, which he established in 1886. [5]

Further afield in Europe’s far south east, another Ottoman mosque received something of a neo-Moorish facelift! Found in North Nicosia, presently the capital of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, the Sarayönü Mosque is perhaps unlike any of its neighbouring counterparts.

With the exception of its traditional Ottoman “pencil” minaret, the mosque was completely rebuilt after an earthquake at the start of the 20th century. [6]

The British architect Fenton Atkinson took on the task of repairing the mosque, and is said to have based its new design on recollections of his time in Andalusia. [7]

The work’s completion is dated to 1903, and the finished product certainly appears to have visible influences that could be traced back to Muslim Iberia, especially in its rows of pointed horseshoe arches that adorn the mosque’s walls and mihrāb.

Back to the source?

One needn’t traverse the sea to find Neo-Moorish architecture.

In fact, it can be found right back where al-Andalus all began, in Gibraltar. The British overseas possession was the point through which Muslim forces first entered Iberia from North Africa in 711, establishing Islam on the peninsula in the process.

How fitting — if not a little surprising — then, that in 1832, an Anglican cathedral sporting Moorish horseshoe arches with alternating colours opened in the territory.

The style was not universally liked by the Anglican clergy.

In 1859, a Dorset vicar wrote,

“…the builder (architect I cannot call him), has crowned his work with an apex of absurdity, by selecting of all others the Moorish style — the style of the arch-enemies of the Cross.” [8]

Nonetheless, the British Chief Engineer Colonel Pilkington, who originally initiated the construction deliberately chose this style to commemorate Gibraltar’s Moorish heritage.

If Colonel Pilkington’s decision re-affirmed al-Andalus’ importance in Iberian history back then, Granada’s recently built Great Mosque has done the same in this century.

Known locally as the Mezquita Mayor de Granada, the house of prayer opened back in 2003, making it the first mosque to open in the city since the fall of al-Andalus in 1492. [9]

The white mosque blends into its surroundings naturally and, though over a century-and-a-half too young to fit into the 19th and early 20th century Moorish Revival period, it beautifully incorporates a range of al-Andalus’ classic motifs.

These are visible right on entry in the mosque gardens, which boast mosaics and a fountain made by Moroccan craftsmen using the same old techniques as the Muslims of al-Andalus would have done a millennium ago.

Moreover, its square minaret has a pointed hipped roof, resembling those of many components of the Alhambra. Perhaps its most show-stopping feature, however, is its intricately decorated horseshoe arch mihrāb, directly inspired by that of the Great Mosque of Cordoba.

Structures like these remind us of a distant but glorious past Islamic civilisation, in which not only Muslims but others also flourished.

As Muslims today who are part of the European mosaic, we should be pleased that al-Andalus carries a legacy that has inspired people — Muslim and non-Muslim across the continent — far beyond its end in the late 15th century.

Crucially, we should feel confident in ourselves, that we too are working towards making powerful and positive contributions to the world around us, that we are re-building that same spirit, inshāAllah.

Action points

-

Think about how we may not witness every victory, but our efforts can outlive us.

-

Consider why non-Muslims admiring and copying Islamic civilisation matters today.

-

Read up on the history of al-Andalus with Ustadh Kashif Zakiuddin’s article: The End of Muslim Spain.

Source: Islam21c

Notes

[1] Diana Darke, Stealing from the Saracens

[3] https://youtu.be/IIvlx2kXiH8

[4] https://www.bradfordsynagogue.co.uk/about-the-synagogue

[5] https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/istanbul-yildiz-hamidiye-mosque-sultan-abdulhamid

[6] https://www.yeniduzen.com/sarayonu-meydaninin-uzak-ve-yakin-gecmisi-80606h.htm

[7] http://www.cypnet.co.uk/ncyprus/city/nicosia/sarayonu.htm

[8] https://www.ministryforheritage.gi/heritage-and-antiquities/cathedral-of-the-holy-trinity-6