In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. All praise is due to Him, and may His peace and blessings be upon His final Messenger, Muhammad.

In 921, the Abbasid diplomat Ahmad ibn Fadlān left Baghdad on a mission to the far north. Tasked with strengthening ties between his master Caliph al-Muqtadir and a revert Muslim ruler a long way from home, the envoy was in for quite a journey.

Thankfully, Ibn Fadlān wrote about his arduous trek, as well as his time in Russia after he arrived at the court of Almish, the Emir of the Bulghār Turks.

He documented his time away in great detail, discussing the weather and the people he encountered. Ahmad shares entertaining anecdotes, for instance how he rode his camel through the intense cold wrapped in so many clothes that he “could hardly move”. [1]

A Muslim wrote history’s earliest record of Viking culture!

Among Ibn Fadlān’s most valuable writings are his fascinating observations of travelling Viking traders.

Staggeringly, he wrote the world’s earliest known record of Viking life and culture as a result of having met them, including the first and only existing eyewitness account of a ship cremation funeral.

It is clear the emissary was not overly enamoured with these merchants. In fact, he went so far as to liken them to “wandering asses”. Nonetheless, Ibn Fadlān’s observations offer a fascinating snapshot of contacts between medieval Muslims and the Vikings.

Better yet, this story can offer an important insight into Britain’s own Viking past, or for that matter, any country claiming Norse heritage.

Almish seeks Abbasid aid

Before we look into why, let’s set the scene first. Why was Ibn Fadlān sent north, and who was this Almish he was meant to meet?

He was the ruler of the Bulghārs, a semi-nomadic Turkic people inhabiting Volga Bulgaria — a kingdom at the confluence of Russia’s Volga and Kama rivers. [2] [3] He ruled over both Muslim and pagan subjects, but was himself a reluctant vassal of the Khazars, another Turkic group whose ruling elite had adopted Judaism, most likely between the late 8th and early 9th centuries.

The Khazars controlled access to both the Black and Caspian Seas from their capital Itil at the mouth of the Volga, adding to their economic and political influence.

Eager to break away from this powerful empire, Almish sought help from the Abbasids, asking the caliph to send a dignitary to educate him and his people in Islam, help establish a mosque, and build a fortress to defend his emirate from the Khazars.

Ahmad ibn Fadlān was part of the Abbasid delegation sent in response. Much to the ire of both men however, an underhanded plot caused Ibn Fadlān to arrive at Almish’s encampment without the funds for the fortress.

Nonetheless Ahmad set about his religious duties, educating the Bulghārs on how the khutbah should be read, encouraging the women to veil in the presence of non-Mahram men (albeit unsuccessfully), and inviting their non-Muslim compatriots to Islam.

In one charming story, he gave da’wah to a man named Talut who accepted Islam along with his family.

The diplomat recounted,

I taught him how to say: ‘Praise be to God!’ and: ‘Say, He is God, the One’.”

…adding how this made the man happier than a king.

Almish, however, was deeply displeased that the money for the fortress was not forthcoming. He even protested by having his mu’adhin call the iqāmah according to the Hanafi madhab instead of the Shāfi’ī way like the Abbasids, directly contradicting Ibn Fadlān’s instructions.

While it is unclear whether he ever received the payment or not, the arrival in Baghdad of a group of Bulghārs intending to make Hajj after the Abbasid visit could suggest that the two sides patched up relations later on.

Meeting the Rūs

It was in 922, during his time in Almish’s territory, that Ahmad came into contact with Viking merchants known as the “Rūs”.

This was by no means the first encounter between Muslims and Vikings. In fact, Norsemen had been raiding and trading in Muslim lands for some time already.

Viking merchants from Sweden first started trading along Russian waterways in the late 8th century. This opened routes to Muslim markets, and even brought them across the Caspian Sea and into Baghdad.

Honey, furs, slaves, swords, and other commodities were among their wares, which they exchanged for Islamic silver. Many valuable silver dirhams have since been found in Viking coin hoards throughout Scandinavia. [4]

Vikings even brought Islamic coins to British shores: a silver dirham from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for instance, has been discovered in Yorkshire! [5] [6]

In other circumstances, Muslims met Norsemen as ferocious foes.

In 844, Vikings attacked the Muslims of Portugal and Spain. According to the chronicler Ibn Hayyan, they looted Seville and “plundered all they could” during their incursion. [7]

An account by the Baghdad-born historian Mas‘udi also reports that decades later, the Rūs “spilled rivers of blood” during raids on Azerbaijan and the wider Caspian region around the year 913. [8]

Thankfully for Ibn Fadlān, when he met these Vikings, they were travelling for business rather than battle.

Initially, Ahmad was impressed by their appearance.

I saw the Rūs, who had come for trade and had camped by the river Itil. I have never seen bodies more perfect than theirs.”

He continued,

They were like palm trees. They are fair and ruddy. They wear neither coats [qurtāq] nor caftans, but a garment which covers one side of the body and leaves one hand free.

Each of them carries an axe, a sword, and a knife and is never parted from any of the arms we have mentioned.” [9]

In addition to their weaponry and clothing, he noticed some had a taste for the finer things.

He recorded, for instance, that the Viking women would adorn themselves with brooches of iron, silver, copper, or gold, and wear gold and silver torques around their necks.

A woman’s husband, he wrote, would have new torques made for her as his wealth increased, meaning some women could end up wearing many at once.

He may have appreciated their physical looks, but Ibn Fadlān was undoubtedly appalled by their lack of hygiene. He even went so far as to describe them as “the filthiest of God’s creatures.”

Every day without fail they wash their faces and their heads with the dirtiest and filthiest water there could be.”

Painting a stomach-turning picture, he described how a group of men would take turns washing their hands, faces, and hair from the same basin of water, each blowing his nose and spitting into it before it was then offered to the next man.

The Abbasid envoy learned about a range of Viking religious rituals and beliefs too.

He wrote, for instance, that the Rūs traders would leave food and drink offerings to idols, hoping this would bring them success in selling their merchandise.

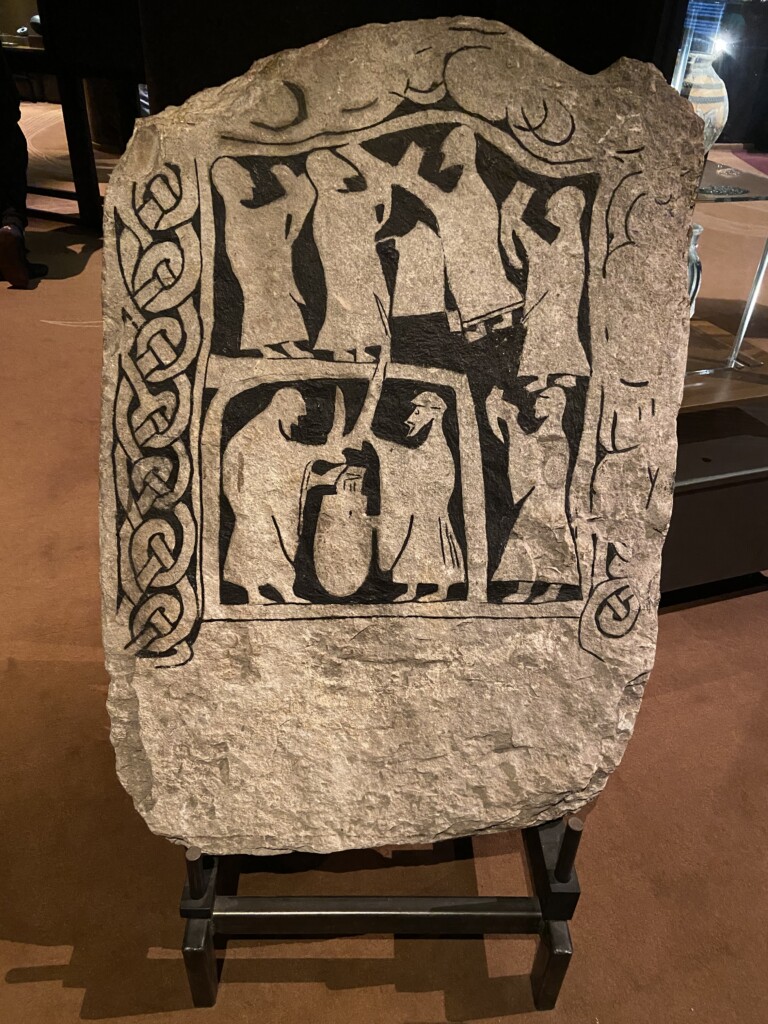

But perhaps the strangest of all the practices he witnessed was the aforementioned funeral, his record of which remains a unique contribution to world history.

The ceremony Ibn Fadlān described was a grim spectacle. He saw the Rūs carry the body of a deceased nobleman onto a boat that had been drawn out of the river and placed on a wooden frame. After laying the dead man on a bed and leaving foodstuffs near him, the Vikings proceeded to slaughter a dog, horses, cows, and chickens, before throwing them all on the boat.

After these gruesome scenes, he would later see two men strangle a slave girl with a cord, while a witch stabbed her with a dagger, in yet another sacrifice.

Thereafter, the mourners set the frame alight, allowing the flames to engulf the ship, cremating the remains of the nobleman and the others on board.

As the boat burned, one of the Rūs struck up a conversation with Ahmad through an interpreter, saying,

You Arabs are fools!”

When Ibn Fadlān pressed him for a reason, the man revealed Viking beliefs about life after death, answering him with…

Because you put the men you love most [and the most noble among you] into the earth, and the earth and the worms and insects eat them.

But we burn them [in the fire] in an instant, so that at once, and without delay they enter Paradise.”

Why is this important to us today?

These historical accounts may be interesting in and of themselves to some, but their relevance to the United Kingdom and other countries claiming Viking heritage is all too clear. In essence, the writings of this Muslim diplomat can help British people to better understand their own country’s history too.

After all, Vikings had a long historical presence in Britain, as raiders, settlers, and rulers.

The Norsemen’s first recorded raid on the island took place in 793. Decades later, they conquered York in 866, ruling until 954 with the death of Eric Bloodaxe, the city’s last Viking king who was himself also a former king in Norway. Four Viking kings would later sit on the English throne between 1013 and 1042. Meanwhile Scotland’s northern Orkney and Shetland Isles have significant Norse heritage as well. In fact, many Scots with links to these areas have Viking names to this day. [10]

And yet, despite the UK’s deep-rooted Viking legacy, it is through Ibn Fadlān’s encounter with the Rūs in 922 on the banks of the Volga that historians have their earliest eye-witness account of Viking culture.

Ahmad’s writings give a valuable look into how the ancestors of many Brits may have lived their daily lives, dressed, traded in goods, practised pagan rituals, and bid farewell to their dead. That this record was originally written in Arabic, may well come as a shock to many today!

Nonetheless, Ibn Fadlān’s contribution to Norse history is undeniable, giving his works an important role to play in enhancing and unlocking our understanding of Britain’s own medieval past.

This begs the question, could knowing this story add to important conversations between British Muslims and our neighbours and fellow citizens? Does it not present opportunities for da’wah and relationship building?

Perhaps the same could be said for Scandinavian Muslims too, especially considering Norway and Sweden’s impressive shows of support for Palestinian rights by recognising the state of Palestine. Could this special link not soften hearts further still?

Action points

-

Grab a copy of Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers to the Far North.

-

When Vikings come up in conversation, mention Ibn Fadlān — it could open the door to da'wah!

-

Use the significant history of Muslim–European trade to foster positive links today.

Source: Islam21c

Notes

[1] “The Book of Ahmad ibn Fadlān 921-922” in Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers to the Far North

[2] Not all Turks are from Türkiye. There are many other people, for instance, Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, and Tatars, who also have Turkic cultural and linguistic backgrounds; the Bulghār Turks are one of these groups.

[3] Today, remains from the state’s old capital (also known as Bolghar) are to be found near another town of the same name in the Russian Federation’s Republic of Tatarstan, which still has a significant Muslim and Turkic population

[5] https://www.caitlingreen.org/2014/12/distribution-of-islamic-dirhams-in-england.html

[6] https://www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/blog/beyond-jorvik-the-vale-of-york-viking-hoard-andrew-woods/

[7] “Ibn Hayyān on the Viking attack on Seville 844” in Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers to the Far North

[8] “Mas‘udi on a Viking raid on the Caspian c. 913” in Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers to the Far North

[9] Here the term “River Itil” refers to the Volga

[10] https://www.history.org.uk/primary/resource/3867/the-vikings-in-britain-a-brief-history