“If a man’s Muslim brother is slandered in your presence, and you are capable of defending him and you do so, Allāh will defend you in this world and in the next.”[1]

UAE’s Foreign Minister, Abdullah b. Zayed Al-Nahyan recently sought to slander the last Ottoman Governor of Madīnah, Fahreddin Pasha (aka Fakhri Pasha) as someone who allegedly had committed abuses against the local population and pilfered property. As the ḥadīth at the outset of this article makes clear, it is imperative for some to defend the honour of the one being slandered.

Background

It goes without saying that Madīnah is an exceptionally important city. It has only come under attack in very rare circumstances; one such occasion was the famous Battle of Uḥud when the Quraysh had intended to destroy the minority Muslim community of Madīnah. Another occasion was the Battle of Khandaq (Trenches) – also known as Ahzāb (Confederates) because along with the Qurayshi polytheists, local Jewish tribes and many other Arab tribes and groups came together to attack the Muslims in Madīnah. A further occasion was in the 12th Century when crusading Christians planned to exhume the blessed body of the Messenger of Allāh (sall Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam) but were thwarted in their attempts by the great Muslim hero and leader of the time, Nūr al-Dīn Zenghi (raḥimahu Allāhu).

What we are able to establish from the above incidents is that those who have attacked Madīnah have always been those who are the enemies of Islām and Muslims.

This brings us on to another attack which took place in the blessed city of Madīnah during the reign of the Ottomans.

Treachery and the Arab Revolt

The impact of the First World War (WWI) is still felt in the Muslim world. Of all the Arab provinces of the empire, it was the blessed city of Madīnah where Ottoman rule lasted the longest, until 10 January 1919. Sultan Selim, the conqueror of Mamlūk Egypt in 1517, was given the honorary title of Khādim al-Haramayn al-Sharīfayn, “Servant of the two Holy Places” (Makkah and Madīnah) from the Nile to the Bosporus. After his conquest of Egypt in 1517, Sultan Selim brought the relics from the Hijāz to Istanbul. They include what is reported to be the mantle of the Messenger of Allāh (sall Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam), his banner, facial hair and other belongings that are today displayed in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul.

The Hijāz (which includes both Makkah and Madīnah) occupied a special place in the territories of the Ottoman Caliphate. This had to do with its spiritual authority and thus its great deal of prestige.

However, the Ottoman Caliphs’ control over the Hijāz from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century was tokenistic to some extent because the Ashrāf (Sharifians) were largely in charge although overall supremacy remained with the Caliph.[12]

Arabia began to play a more important role for the Ottomans during the reign of the last great Caliph, ʿAbdulhamid and his Pan-Islamic policy in the second half of the 19th century. The symbol of this policy was the Hijāz Railway. The main purpose of the railway was to establish a connection between Istanbul, the seat of the Islamic Caliphate, the Hijāz, the destination of the annual Ḥajj pilgrimage, and Damascus. Another important reason was to improve the economic and political integration, unity and brotherhood of the distant Arabian provinces into the Ottoman state, and to facilitate the transportation of military forces.

The Sharīf of the time, Ḥussein b. ʿAlī, considered the Hijāz railway a threat to his rule. Accordingly, since July 1915 he had been engaging in negotiations with Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, where Hussein agreed that his Hashemite family would lead a nationalistic, Arab rebellion against Ottoman rule in return for British pledges of recognition of the Hashemite leadership over the ill-defined Arab Kingdom.[2] The Sharīf was of importance to the British for several reasons, one of which was that they considered him to have religious authority in order to counteract the Jihād that had been declared on the British empire by the Ottoman Caliph, Mehmet V as part of their participation in WWI (it should be noted this declaration remains the last ever proclamation of Jihād in history by a Caliph). It would also serve to tie down the Ottoman forces in the Hijāz preventing them from reinforcing the Palestinian front, which the British had their eyes firmly fixed on hoping to reconquer that which they were unable to do since their defeat during the Crusades.

With the devilish deal completed, Sharīf Hussein declared the Arab revolt on 5 June 1917. Makkah and Jeddah were taken very quickly. Madīnah, however, proved to be more difficult and one man stood in their way. The offensive of the Sharifian troops on the railway near Madīnah was not only repelled, but Ottoman forces even pursued their attackers under the command of Fahreddin Pasha who, along with his Hijāz Expeditionary Force, had only arrived in Madīnah a week before the outbreak of the hostilities. Altogether, his troops were reported to have numbered around 14,000 men and were considered a formidable force.

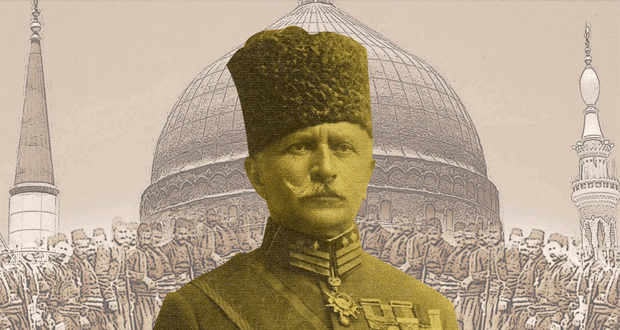

Fakhri/Fahreddin Pasha and the Siege of Madīnah

Fahreddin (aka Fakhri) Turkkan was born in Rusçuk (present day Bulgaria) in 1868. He attended the Mekteb-i Harbiye (War Academy) and assumed several commands in the Balkan Wars. At the outbreak of WWI, he became the deputy of the Commander-in-Chief of the Fourth Army, Ahmed Cemal Pasha. In 1916 he became Commander of the Hijāz Expeditionary Corps. Nearly 50 years old at the time, Fahreddin was considered a very capable commander and an excellent soldier who could motivate his troops.

In late 1916, Fahreddin Pasha felt strong enough to launch a full-scale assault to recapture ground they had lost. However, it was only due to Britain’s Royal Navy’s support of the treacherous rebels and logistical problems among Fahreddin’s forces that they were unable to do so and were forced to retreat to Madīnah in mid-January 1917.[3]

Madīnah was proving difficult for the Sharīf and his British backed forces to conquer and until such time that it was taken, the Sharīf’s objective in being declared as the “King of Hijāz” was not accepted. Also causing worry for the Sharīf was that to the south, tribes threatened to renounce their loyalty to him. The centre and east of the Peninsula (Najd) was under the control of the rivals of the Sharīf, who were their equals in treachery to the Ottoman Caliphate. The Āl-Saud were also doing deals with the British who, in turn, were also promising them leadership of Arabia in return for their support in overthrowing the Ottomans. As such, the Sharīf’s men, backed by the British including officer T.E. Lawrence, intensified their attack and the Hijāz railway, which served as an umbilical cord connecting the Ummah (global Muslim community) from Istanbul, Syria and Madīnah, was heavily attacked.

Meanwhile, in the first half of 1917 when Baghdad was already lost, the British pressed on in their advance at the theatre of war in Palestine. The Ottoman leadership hesitated at first because the voluntary surrender of one of the Holy Places in the middle of a war would have had a devastating effect on public opinion. A march which was sung at the time in schools and in the army illustrates their attachment and commitment to Islām and Madīnah:

“We will not leave the one who rests in Madīnah [the Prophet], we will rather die and rescue the motherland”.[4]

Having lost trust in Sharīf Hussein after his revolt, the Ottoman government tried to replace him with his cousin—Ali Haydar—a member of a rival clan. However, Haydar was recalled not even a year after his arrival, and his farewell words to Fahreddin were:

“The protection of this Tomb [of the Prophet] is in the hands of Allāh, but you are His instrument. I leave it in your care. Be worthy of the trust”.[5]

With Fahreddin and his men held up in Madīnah, the British forces took Jerusalem in December 1917 and Damascus was captured in October 1918. Growing impatient with progress in Madīnah, Sharīf Hussein sent a letter to Fahreddin with the demand that he surrender. Fahreddin responded to Hussein addressing the letter with: “To Him who broke the power of Islām”. He related a dream to Hussein in which the Messenger of Allāh (sall Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam) had told Fahreddin to follow him. He ended with these lines:

“As I am now under the protection of the Prophet and most high commander, I am busying myself with strengthening the defences and the building of roads and squares in Madīnah. I beg you not to trouble me with useless requests.”[6]

In late September 1919, Reginald Wingate, High Commissioner to Egypt, also demanded Fahreddin to surrender. Fahreddin responded firmly:

“I am an Ottoman. I am a Muslim. I come from the family of Balioğlu. I am a soldier.”[7]

Fahreddin was resolute in his intention that he would not surrender, but would defend Madīnah up to the last bullet and the last man.

The military resistance of the Ottomans and their German ally collapsed in October 1918. On the 30th October the armistice agreement was signed in Mudros which brought the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottomans and the Allies of WWI to an end – this included that the Ottoman garrisons in the Hijāz, Asir and Yemen were to yield to the next Allied commander. News of the agreement reached Fahreddin who remarked that he could not accept that:

“the weapons we had protected with our sacrifices would have to be laid down at the feet of barelegged Bedouins and a captain [the British captain, Garland] who had insulted our honour… even if the occupying allied powers turning Istanbul upside down, it would not change my sacred decision [to defend Madīnah]”.[8]

For Fahreddin, he was not going to accept anyone’s words and made clear that he would only surrender on the decree of the Sultan.

On the morning of 9 January 1919, a delegation from the Ottomans visited Madīnah to persuade Fahreddin to accept the terms of surrender. Fahreddin had, however, retired to the Prophet’s tomb. There he was finally arrested by his own men and the siege was thus brought to an end.

A report by Sadiq Yahya, a colonel in the Egyptian Army, arrived with the Sharifian Forces in Madīnah stating that the city was “in good order”. He also commented that even the agriculture had been taken care of. Yahya gives an account of the wanton destruction and looting that was carried out in Madīnah by the Sharīf’s troops and remarked that “the natives of Madīnah lost more during the first 12 days of the Arab occupation than they did during the two years it was in the hands of Fakhri Pasha”.[9]

Fahreddin was subsequently taken to Egypt as a prisoner of war and later exiled to Malta and held captive for two years. After his release in 1921, he was posted as an ambassador of Turkey to Afghanistan from 1922-1926. He retired from service in 1936 and died in 1948.

Points to Note:

We can only speculate today what might have been the case had Fahreddin and his men not been besieged in Madīnah and were stationed at the Palestinian front.

There are some people who, on account of their deeds or misdeeds, are honoured or dishonoured with a title by which they are forever remembered. For example, ʿAmr b. Hishām eternally being remembered as Abū Jahl (the father of ignorance), the false prophet Musailamah as Musailamah al-Kathāb (the liar); or Muḥammad b. Murād being Muḥammad al-Fātih (the opener or conqueror) and Yūsuf b. Ayyūb being Salāh al-Dīn (righteousness of the faith). Similarly, we find Fahreddin forever being referred to with the honourable title of ‘Defender of Madīnah’, and thereby earning a heroic place in the hearts of Muslims.

Some will, however, point to the fact that Fahreddin served under the Community of Union and Progress which dethroned the last great Caliph, Abdülhamid in 1909 – although Caliphs were still appointed after Abdülhamid until 1924, their roles were nominal token positions. It is also correct that, in contrast to Abdülhamid’s pan Islamic policies, the CUP that took control of the Ottomans were pursuing a more nationalistic, Turkish agenda. However, it must be made clear that the CUP that had arisen from the Young Turk movement was initially a triumvirate regime that comprised of the ‘Three Pashas’, namely Enver Pasha, Taalat Pasha and Djemal Pasha. It would be wrong to assume the Three Pashas would have followed the same course of Ataturk, who later took control of the Young Turk movement. The Three Pashas were equally proud of the caliphate and wanted to restore it to its past glory and still associated with Islām. Ataturk however took over, had these men removed and pursued his own path where there was to be no association with Islām.

As for Fahreddin, to seek to question his legacy by associating him with Ataturk, under whose administration he continued to work for some years after the dissolution of the Caliphate before retiring, is to some extent akin to questioning the legacy of Salāh al-Dīn for working under the administration of the Fatimids in Egypt.

We should judge Fahreddin for what is clearly documented of his own words from his correspondence at the time from which we can establish unequivocally that he considered his role in defending Madīnah a religious duty. His letter to his superiors wherein he made clear that even if the Ottoman city of Istanbul were razed to the ground by the enemies, he would not deviate from his mission in defending Madīnah, is evidence that Fahreddin was not a nationalist – for the nationalists, Turkey was the motherland that was to be put before all else. We can also ascertain the value that Fahreddin still placed on the nominal Caliph as he was not prepared to accept anyone’s orders except the Caliph’s.

Also, after the war, Fahreddin was an ambassador to Afghanistan (1920-1926) where he was involved in the collection of donations from Afghans and Indian Muslims for Turkey’s war of independence – a foundational pillar of the Central Khilafat Committee and broader Indian Khilafat movement.[10]

Whilst it is correct that Fahreddin had taken some valuables which were housed at the Haram al-Sharīf in Madīnah back to Turkey in the same way as Sultan Selim had done in 1517, Fahreddin’s reasons for taking them were to protect what he considered to be objects of Islamic importance from the British – had he not done so, it is very likely that the items today would be displayed in the British Museum.

The crime of the Sharīf and others that had committed treachery is best summed up in the words of the British historian, Phillip Robins who said that they had “eschewed Islamic solidarity of the Ottomans in favour of dynastic ambition”.[11] It is also worth remembering that none of the Arab units of the Ottoman Army defected to Sharīf Hussein. The majority of Arabs remained loyal to the ideological foundation of the Ottomans, which was, in Robin’s words, “loyalty to the centre in the name of Islām.”

The story of Fahreddin is relevant today as we continue to see many Muslim “collaborators”. One of the strategic goals of the European powers was to destroy the Caliphate. This institution, established by the Companions of the Messenger of Allāh (sall Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam) to provide historical continuity to Islām, survived 1,300 years of turbulence. Not even the savagery of the Crusaders or Mongols could extirpate it but in the end, the treachery of the Arab revolt, and the Young Turks in Turkey, resulted in the abolishment of the Caliphate. Today, we see collaborators in the Muslim world such as some Gulf regimes forsaking Palestine, or self-professed “liberal Muslims” contributing to the deformation of Islām to make it more compliant to western powers. In each case, they should ponder on what happened to Sharīf Hussein who himself was pushed aside by the British, after carrying out their orders, in favour of the Sauds.

It is as Ertrugul Gazi says in the drama series Dirilis Ertrugul:

“The arrow that strikes the eagle is usually made from its own feather.”

[donationbanner]

Source: www.islam21c.com

Notes:

[1] Baghawi;

[2] Kedouri, Elle (2014) ‘In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and it;s Interpretations 1914-1939’;

[3] Strohmeier, Martin (2013) ‘Fakhri (Fahrettin) Paşa and the end of Ottoman rule in Medina (1916-1919)’;

[4] Ibid;

[5] Stitt, George (1948) ‘A Prince of Arabia’;

[6] Strohmeier, Martin;

[7] Ibid;

[8] Ibid;

[9] Kedouri, Elle (1977) ‘The Surrender of Medina, January 1919’;

[10] Ahmed, Faiz (2017) ‘Afghanistan Rising: Islamic Law and Statecraft between the Ottoman and British Empires’;

[11] Robbins, Phillips (2003) ‘Suits and Uniforms: Turkish Foreign Policy since the Cold War’.

[12] The descendants of the Messenger of Allāh (sall Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam) from the clan Hāshim (Hashemites) and the tribe Quraysh.

can i take this details and make a video out of it