Places of worship are likely to be allowed to open for congregational prayer from the 4th of July. However, most mosques are registered charities, and regardless of what the government says, they must take their own steps and precautions before opening. Failure to do so would mean that they are likely to be in breach of their duties under charity law, as well as health and safety law. Ultimately, it will be charity trustees who will be held responsible for any failings, and in some circumstances they could be removed as trustees.

There are around 1730 mosques in this country, and no two are the same. The vast majority are not large mosques, but instead are smaller local mosques. Each mosque is different in terms of size, location, type of mosque committee, finances, and human resources. As someone who visits and audits mosques regularly, I know full well that this next period will be a real challenge for many mosques. In most cases, when we carry out an audit, we are the first to do a health and safety risk assessment for the mosque. However, with some well-planned risk management controls, many mosques should be able to open safely.

For the majority of mosques, this will be the first time they have had to deal with a major public health hazard that can lead to serious disease and death. As followers of Islam, the overriding priority for the management of mosques must be the protection and preservation of human life. If a mosque committee feels it cannot manage and control the risks, it should not be pressurised to open the mosque until it is ready. Similarly, it should not hesitate to close if the Covid-19 infection rate becomes high in the area.

The following is a simple guide to get to a position to make decisions to re-open mosques safely.

1

The government has already published some guidance and is likely to publish more before the 4th of July. Mosques should be aware of this guidance. We are in a time of a major public health hazard, and the nature of risks are already known and may change. The disease spreads through droplets from the nose and mouth and personal contact/touch, and especially close contact (within 2 metres). These are the areas to focus on.

2

The first step would be for trustees (and their management committees) to meet to discuss and document how they will evaluate and manage all the risks. This not only includes the public health risks that have already been identified, but also financial and human resources risks. Should trustees need more information, I have produced a presentation that can be used as the basis for discussion at such meetings. This is available on request for mosque trustees by emailing [email protected]

3

There are other areas of mosque activity, such as the Madrasa, hall hire, and staffing. We recommend that these areas remain closed until September. Charities need to consider the impact on their furlough payments if staff return to work before October, and also the need to produce a health and safety risk process under health and safety law for staff before they can safely return to work and their duty of care to volunteers.

4

As this disease is likely to be around for a couple of years at least – unless a vaccine is produced – mosque committees should make it their business to know what their local infection rate and death rate is, and monitor these rates on a weekly basis. They should also be aware that Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) communities have a higher infection rate and death rate than others, so the risk to our communities is higher. There are now ways to check the locations of the deaths in your area by typing in your postcode.[1] This is an important part of risk evaluation. A mosque in a small town in North England with a small congregation and a low infection rate will face a much lower risk than, say, a mosque in East London with a large capacity and a higher infection rate. The public health risk cannot be eliminated totally. The aim should be to reduce the risk as much as possible by reducing contact and touch, as well as reducing people in high-risk categories from coming to the mosque.

5

Assess the location of the mosque. Many mosques have on-street access at the front or back of the mosque, and since queuing is likely, this will represent a risk to the public. The street/footpath/road do not belong to the mosque, so the mosque must control the risks on these public areas that will be caused by the mosque. Queuing and congestion should be contained within the premises if possible.

6

Mosques should first work out their normal prayer capacity and Covid-19 capacity (praying with a 2-metre distance between worshippers). This should be done for Friday and daily prayers. The 2-metre distance is approximately three household prayer mats. As a rough guide, this represents around 20% of normal capacity. So, for a Friday congregation of 200, this will be 40 people, and for 1000, around 200 people (depending on shape and access of the mosque). Mosques might wish to consider using car parking areas to increase capacity and increase the Jamā’a. Numbers for daily congregation prayers in most mosques are not usually more than a few rows and should be easily manageable.

7

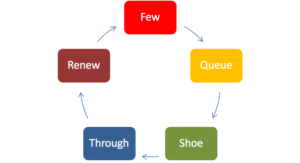

We have developed an easy to remember formula for mosques to identify key areas where risks need to be controlled and managed.

8

Few: Given the reduced capacity, the aim should be to contain the numbers of the congregation to the new Covid-19 capacity and avoid high-risk groups from entering the mosque. This can be done in many ways. For example, by identifying clearly a list of exclusions, such as healthcare workers, care workers, taxi drivers, those who have been out of the country or travelling to other parts of the country. These groups are more likely to have come into contact with someone who has the virus and pass it on. Others may wish to do this by age, membership, and those with medical conditions. In each case, the decision needs to be justified, otherwise it may breach other laws such as those on equality. Do include disabled and women’s access in your plans. The general message should still be: pray at home if you can (especially those in high-risk occupations and categories). Make sure to widely advertise the exclusions. Mosques will need to have a plan for how to deal with too many people turning up.

9

Queue: We all know the problems of congestion and bottlenecks at the mosque, with people coming in and out. This will have to be managed carefully. Barriers and 2-metre markings will have to be made and controlled. This may not be as challenging if your capacity is 40-100 people at each prayer. We recommend that no one is allowed in without a mask, clean gloves (plastic or cotton), and clean socks. Whilst some have recommended prayer mats, we think it is possible to have other disposable paper solutions to partially cover prayer areas. There are a range of temperature check devices that are available, from mass scanners to the simple handheld medical type. These may also be considered depending on numbers, and are often used in other countries at, for example, entrances to supermarkets.

10

Shoe: Shoe areas in mosques tend to be poorly managed, disorderly, and usually form a bottleneck. We suggest that worshippers come to prayers not in laced shoes but instead slip-on shoes or sandals. Worshippers should be given plastic bags for their shoes, as at Eid prayers. They should keep the footwear next to them at prayer and then leave with them.

11

Through: When going through the mosque, 2-metre markings should be placed throughout the circulation, reception, and prayer areas. People should avoid touching common areas such as stair handrails – notices should state this. The aim should be to get people in and out as soon as possible. The Khutba and prayers should be limited to 15 minutes if possible. If there are large numbers, exits should be controlled, preferably by a separate door. Any items of common touch, such as the tasbīh, Qur’ān, and caps should be removed. Cash collections should be avoided or counted with gloves. Air conditioning and fans should be switched off, but windows and doors should be opened for circulation. Wudu areas should remain closed to the public.

12

Renew: Aftercare is equally important. Any common areas must be disinfected, and carpets cleaned. If an incident or breakout has been identified to the mosque, we recommend a deep clean using a professional company. Procedures should also be reviewed and updated.

13

Remember that it is important to record and document how you discussed and evaluated the risks and how you made your decisions. These will be central to any Charity Commission or legal investigation or claims against you and for your insurance purposes. Please make sure the health and risks to your staff and volunteers are also considered and mitigated. We recommend that all staff and volunteers are clearly trained on procedures and how to maintain control. In certain circumstances, if a Covid-19 incident or loss (death or financial) occurs at the mosque, this may need to be reported to the Charity Commission. Similarly, any investigations for breach of emergency laws by the police, or suspected Furlough abuse by HMRC, will also need to be reported to the commission. The guidance is complex, so for specific incidents speak to a specialist charity adviser or the Charity Commission.

[box type=”download”]

Be safe and pray safe. Contact us if you need further advice or support. A video recording of a recent presentation and talk we gave elaborating on this subject is available online at:

[/box]

[donationbanner]

Source: www.islam21c.com

Notes:

Jahangir Mohammed is CEO of Communica and a charity and mosque specialist. He can be contacted at [email protected]

©Copyright 2020 Jahangir Mohammed

All rights reserved. This publication, or any part of thereof, may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author.

This article is ridiculous – admin please delete.

Congregational prayers with gaps is completely unacceptable, as is not allowing someone into the masjid because they are a taxi driver.

There are a number of other very serious concerns with these recommendations:

– is Fard salat performed with distancing, whether 2m or something else, valid and considered as salat in jamaat? If not, there is absolutely no point in opening masajid and praying apart for Fard salat. This will be bidaa and misleading people. Before starting the Fard salat, Imams always call the congregation to straighten the rows and stand shoulder-to-shoulder and don’t leave any gap. There is a reason for this. Furthermore, the scientific studies on distancing must be considered. There doesn’t seem to be strong unequivocal scientific evidence that this is an effective measure and there is increasing call from many quarters to scrap this distancing guideline.

– how can we discriminate who attends the house of Allah? The house of Allah, if open, must be accessible to everyone who wishes to attend. If people are unwell or feel that they are vulnerable, they should stay away voluntarily.

– what is the point in opening the masajid and asking people to pray at home if they can?

– asking people not to donate cash is clearly a disproportionate suggestion. It will prevent a lot of people from donating money to their masjid and performing acts of sadaqa. The person handling the collection can simply wear gloves.

– regarding the recommendation asking people not to touch surfaces, imagine someone going down the stairs falling down and breaking their back as a result of not holding the handrail because they have been told not to. This is a health and safety issue to consider.

The re-opening of masajid must be given very careful consideration. The preservation of life and health and safety are certainly of paramount importance but there are also the Islamic objectives and prerogatives of the masjid to be considered. If these two things cannot be reconciled, clearly there is no point in opening masajid. Also, government guidelines and, more importantly, regulations must be robustly challenged and must be demonstrated to be evidence-based before they are adopted and used to change the way a masjid functions and, more importantly, the way we worship.

I actually disagree with the two meter salah rule many scholars have said this is harram a innovation that needs to be rejected

I think it is better not to open the mosque until we can pray salah properly without this 2 meter nonsense

Thank you for your personal opinions but many scholars throughout the world have clarified that attending the congregation with gaps is far better than leaving it altogether.

https://mobile.twitter.com/solyman24/status/1265750042608107523

Which scholar has said it’s ‘harram’?

In Islam there are standard laws and laws based on circumstances; there is an principle In Islam that restriction is removed by necessity.